Ape Canyon is a gorge near Mount Saint Helens, Washington, USA. And if you’re wondering how it got such an intriguing name, on a continent with a distinct lack of apes (at least officially), then you’re in the right place.

This blog marks the 99th anniversary of the Ape Canyon attack, which either took place on 16th July 1924, or was reported on that date via an issue of The Oregonian, depending on the source.

Either way, in July 1924, a group of five miners were taking overnight shelter in their hand-built cabin deep within the canyon. As they settled down for a meal and coffee, and perhaps something stronger, the cabin began to be pelted by sizeable stones and rocks. The miners described their attackers as ‘mountain devils’, and it didn’t take long for the band of men to realise they were surrounded.

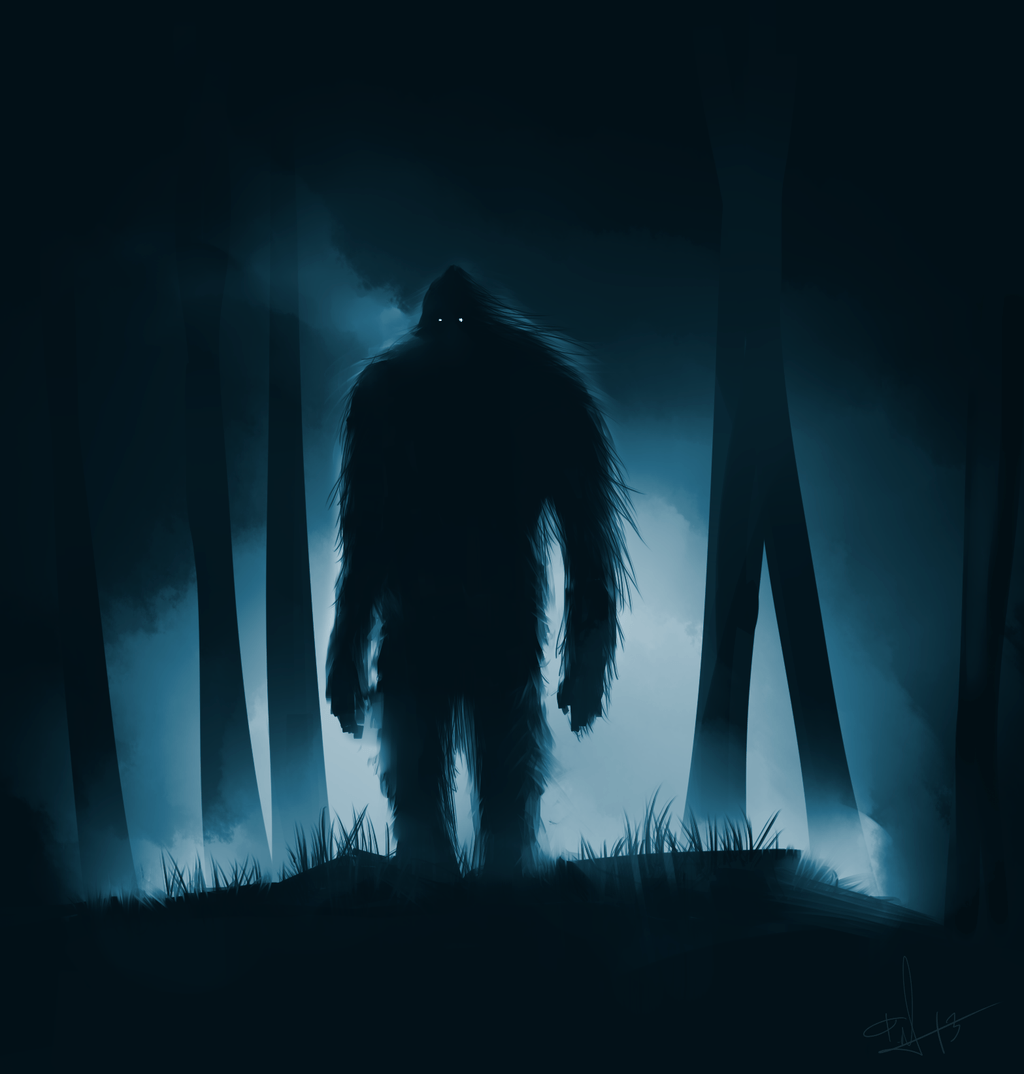

Being hardy folk, and well used to the everyday threats they faced working in the wilderness, the men were armed – and they returned the rock showers with volleys of rifle fire. Each time they did, the sasquatch-like creatures would slink away into the treeline, only to resume their attacks minutes later. They also must have been very close to the makeshift cabin, as it is detailed one of the creatures reached through a hole in the wall and tried to steal an axe, only to be stymied before it could retrieve the weapon fully.

The attacks continued relentlessly until daybreak when the men finally felt able to leave the cabin. Fred Beck, one of the prospectors taking shelter, described seeing one of the creatures in the distance, at the edge of what is now Ape Canyon, and fired at it. His aim is apparently true, as he describes watching it tumble back into the gorge.

Beck would later write a book, titled ‘I Fought the Apemen of Mount St. Helens’. This was published in 1967, amidst the bigfoot furore of that period.

Sceptics, including William Halliday, Director of the Western Speleological Survey, claim that the assailants were in fact local youths. A fireside story, shared by generations of counsellors at the nearby YMCA Camp Meehan on Spirit Lake, was that it was young campers absentmindedly throwing pumice stones into the canyon, not realising there were miners camped in its bottom. He suggests that looking up, the miners would have only seen moonlit figures throwing stones at them, and the narrow walls of the canyon (as little as 8 feet/2.5m at one point) would have distorted voices into something unrecognisable and frightening.

However, this does not take into consideration the eyewitness accounts, including the shooting of a creature, and that hairy hand coming into the cabin.

Perhaps the more sinister alleged encounter involves the disappearance of Jim Carter in 1950. An accomplished skier and mountaineer, Carter was part of a group of 20. The story appeared in an August 1963 issue of the Longview Times by Marge Davenport, titled ‘Ape Canyon Holds Unsolved Mystery’. It was then also included in Roger Patterson’s (yes, that Roger Patterson) 1966 book ‘Do Abominable Snowmen of America Really Exist?’.

An abridged version of the story is below.

‘Carter’s complete disappearance is an unsolved mystery to this day,’ declared Bob Lee, a well-known Portland mountaineer… ‘Dr. Otto Trott, Lee Stark, and I finally came to the conclusion that the apes got him,’ said Lee seriously… On the way down the mountain, he [Carter] left the other climbers at a landmark called Dog’s Head, at the 8000-foot (2400 m) level. He told them he would ski around to the left and take a picture of the group as they skied down to timberline. That was the last anyone saw of Carter. The next morning searchers found a discarded film box at the point where he had taken a picture. From here, Carter evidently took off down the mountain a wild, death-defying dash, ‘taking chances that no skier of his calibre would take unless something was terribly wrong, or he was being pursued… He jumped over two or three large crevasses and evidently was going like the devil.’ When Carter’s tracks reached the precipitous sides of Ape Canyon, the searchers were amazed to see that Carter had been in such a hurry that he went right down the steep canyon walls. But they did not find him at the bottom… ‘We combed the canyon, one end to the other, for five days. Sometimes there were as many as 75 people in the search party ….’ After two weeks the search was called off.

However, again, there is some debate over the exact facts. The Madera Tribune edition of 23rd May 1950, features a small column, announcing a search for a Joe Carter, aged 18. Whereas the 25th May edition of the San Bernardino Sun of the same year (see below), seems to confirm both that Carter’s first name is Joe and ages him at 32. It is in this article Carter is described as an experienced mountaineer, but also suggests he is diabetic. It’s also where we find the link to the original Ape Canyon legend.

You can see there are discrepancies in the details and even the location reported some 13 years after the event.

It is well known that an employee based in a ranger station enjoyed leaving fake tracks along the shore of the aforementioned Spirit Lake. Patterson too has also been long-suspected of pulling off perhaps the best executed hoax in bigfoot lore – and at the very least, I don’t think it’s unfair to suggest he wouldn’t let the facts get in the way of a good story, as here with Carter.

Therefore, it’s difficult to lift the facts from the legendary lore of Ape Canyon. I cannot find any reliable reference as to what Ape Canyon was known as before, or when exactly it took that name – but it joins countless others across the USA associated with bigfoot legends. Today, ever changed since the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, there is a popular hiking and mountain bike trail making the area much more accessible, and a local scout brigade use the Ape Caves as a hangout. But maybe, just maybe, a more sinister troop of unknown creatures still lurks down in the canyon that takes their name.