From the hills of Wales to the heathlands of Dorset, reports of large, unidentified cats continue to surface across the British countryside.

Most are brief encounters. A shape crossing a field. A dark animal slipping through woodland. A dog walker forced to stop mid-stride as something far larger than a domestic cat disappears into the hedgerow.

These reports are rarely treated seriously in the national press. Often they appear in the odd-news columns or alongside stories about mythical creatures and folklore.

Yet they refuse to disappear into the shadows alongside their subjects. And over the past few months, several new sightings have once again brought Britain’s big cats back into the open.

A Panther Prowl’s Ed Sheeran’s Estate.

One of the most widely circulated reports recently came from Suffolk, where a large black cat was seen near the £37 million country estate of musician Ed Sheeran.

Witnesses described a large dark animal moving across farmland close to the property. The sighting prompted speculation that a so-called “panther” might be roaming the countryside and the story travelled quickly through national and international media, largely because of the celebrity connection.

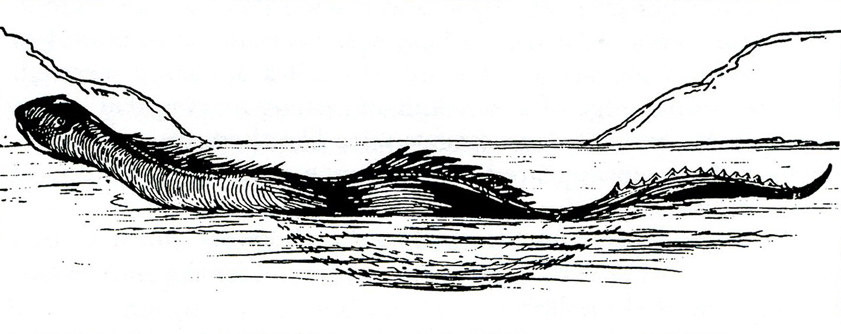

But aside from the location, the details themselves were familiar to anyone who has followed the phenomenon for long. A large, dark cat moving with fluid, purposeful motion, low to the ground. Exactly the sort of description that appears again and again in regional sightings.

Cats Across the Countryside

All over Britain, similar reports continue to surface.

In Dorset, a sighting on Canford Heath near Poole described what a witness believed to be a black panther moving through open heathland.

In Wiltshire, a dog walker near Chippenham reported encountering a large cat on a popular countryside footpath. The witness described an animal significantly larger than a domestic cat, with a long tail and dark colouring.

Further west, a report from Newquay in Cornwall described a large cat seen at distance moving across farmland. Cornwall has long been one of the regions most frequently associated with Britain’s “phantom cats”, often linked with the legend of the Beast of Bodmin Moor.

In North Wales, motorists and walkers have also reported large feline shapes crossing rural roads or moving along field margins. One witness claimed the animal they saw was nearly the height of a car bonnet as it passed through the roadside vegetation.

These accounts vary in detail, but the core descriptions tend to be remarkably consistent.

A powerful, long-tailed cat – often dark in colour, but tan and other hued cats are also reported, seen briefly before disappearing into woodland, scrub, or across farmland.

A Long History of Sightings

Reports of large cats in Britain are of course, nothing new.

Newspaper archives contain sightings dating back decades, particularly from the late twentieth century when stories of “phantom panthers” became a recurring feature of rural folklore.

Many researchers have suggested these reports may trace back to the Dangerous Wild Animals Act of 1976, which introduced licensing requirements for keeping exotic animals. The persistent theory is that a number of privately owned big cats may have been released into the countryside when the law came into force. Since then, further releases and escapes have contributed to more recent sightings.

We might not have direct hard proof or evidence. But, given the scale of the exotic animal trade – both legal and illegal, and the lack of funding to check on many privately-owned animals and licensing both back then and even more so today, it’s not without merit.

And sightings have never stopped.

From Exmoor and Dartmoor to the Surrey Hills, the Welsh countryside, and parts of Scotland – reports of large cats have popped up year in, year out, and continue.

Missed by the Media

Despite the number of sightings over the years and the many reliable witnesses, which include respected journalists and presenters like Clare Balding, the subject is rarely treated with much seriousness in mainstream media.

Often it appears in the same category as folklore creatures or mythical monsters.

The BBC’s Countryfile, for example, recently included Britain’s phantom cats in a list of “mythical beasts”, placing them alongside legendary creatures rather than unexplained wildlife reports. This framing shapes how the subject is perceived.

Instead of examining witness testimony, ecological plausibility, or historical context, the discussion often becomes a curiosity piece – something to be lightly dismissed rather than investigated.

Yet eyewitness testimony remains one of the primary ways wildlife is documented in many parts of the world.

The same observational accounts that guide conservation surveys in remote landscapes are often treated very differently when they occur in the British countryside.

Panther or Puma?

Another recurring problem is species confusion.

Many reports describe a black big cat. But media coverage frequently labels these animals as pumas. The issue with that identification is simple: pumas do not occur in black form. There are no verified melanistic pumas anywhere in the world.

Black big cats, commonly called “black panthers” – are usually one of two animals: leopards or jaguars. In Britain, the most plausible identification would be melanistic leopards.

Leopards are adaptable animals capable of surviving in a wide range of habitats, from rainforest to semi-arid environments and mountainous regions. They are also far more likely than most big cats to survive undetected in fragmented landscapes.

Pumas too, also known as mountain lions and a myriad of other names, are some of the most adaptable cat species, found from the Florida everglades to the high plains of Chile and the deserts of Arizona.

Why Some Researchers Look to Malaysia

If Britain does host a small surviving population of melanistic leopards, one intriguing possibility involves the Malayan leopard.

In the rainforests of the Malay Peninsula, south of the Isthmus of Kra, melanism is extremely common. In fact, the majority of leopards in this region are black.

Interestingly, this detail surfaced while researching my current novel Predatory Nature, where the history of exotic big cats imported into Europe during the twentieth century led me down a rabbit hole into the unusual genetics of Malayan leopards.

These cats are also smaller than many other leopard subspecies, which historically made them attractive to exotic animal collectors and the trade supplying them.

During the mid-twentieth century, when keeping exotic animals became fashionable in parts of Europe and especially the United Kingdom, animals described as “black panthers” were imported from Southeast Asia, to the point that the population was significantly impacted. And today, the population is dominated by those sporting the melanism gene.

The smaller size of the Malaysian sub-species helped fuel the mistaken belief they would be easier to manage. In reality, of course, a leopard is never a domestic animal.

But if any such cats were released or escaped decades ago, their melanistic coats would have offered a natural advantage in Britain’s woodland landscapes, particularly in low light, where their rosette markings are almost invisible – which is a factor that should be taken into account when witnesses describe cats as “jet black”.

Mystery in the Hedgerows

None of this proves definitively that Britain currently hosts a breeding population of large cats.

Most sightings could still have more mundane explanations: misidentified dogs, escaped exotic pets, or fleeting glimpses of ordinary wildlife seen in poor conditions.

Everyday domestic cats are also likely culprits. The recent Devon sighting is a possible example. Despite gaining significant coverage in the press, and comparisons to the Beast of Bodmin in neighbouring Cornwall – the animal in this video moves like a domestic cat, and has the head shape and movement in line with this. However, the published video quality is very poor and it is very difficult to make any kind of certain identification. A feral cat, which can grow to larger sizes, is also a likely possibility.

But the persistence of the reports and the consistency of many descriptions keeps the question alive and shouldn’t be dismissed or derided.

There’s a good chance the truth lies somewhere between folklore and biology. It’s not just possible, but likely, that there are a small number of big cats of more than one species surviving quietly in remote pockets of the British countryside.

Combined with the enduring human instinct to see shadows move at the edge of the woods and wonder what might be watching back, it’s unlikely reports are going to disappear.

Either way, Britain’s phantom cats remain one of the country’s most enduring wildlife mysteries. And every now and then, someone sees something crossing a field that refuses to fit neatly into the explanations we already have.