I recently picked up a 50th anniversary copy of James Herbert’s ‘The Rats’ – a series of books I was borderline obsessed with when I discovered them in my early teens. Despite being slightly alarmed at the inappropriate content that I somehow missed as a kid, and wouldn’t get past an editor’s desk these days (a teacher thinking of 14-year old girls as crumpet!), it still has me gripped no matter how many times I’ve read it.

In ‘The Rats’, the first of the trilogy, there is a harrowing scene of a school under siege – something I wanted to pay homage to in my own first novel, Shadow Beast.

If you’ve yet to read Shadow Beast, there are some mild spoilers hinted at in this chapter, but not completely given away.

I’ve always had a vision that if the book were ever made into a movie or a series, at least one of the scenes from this chapter would feature ‘Bless the Beasts and the Children’ by The Carpenters playing over the muted action – perhaps as the beast stalks past the classroom windows in slow motion, it’s gruesome prize carried in its jaws.

So, here, in a hopefully to become relatively regular feature I’m naming ‘Chapter Tuesdays’ – here is my homage to classic British horror.

Chapter Twelve

Louise Walsh looked out over the playground from her classroom window. The afternoon play break was nearly over, and she watched as the children finished up their games of chase and hopscotch. A small group of them huddled in one corner, no doubt playing on their portable games machines. At least they’re out in the fresh air, she thought. The small primary school in Cannich was a beautiful stone building that had originally been a church. The traditional layout had been put to good use, with the three rooms that came off the main hall now serving as the classrooms for the different age groups the children were separated into.

Louise had the eldest group – the nine to eleven year olds. Her elder colleagues, Mrs. Jones and Mrs. Henderson, took the younger groups of the fives and the sevens. Amongst other things, Louise was also the acting Headmistress. With such a low intake of children and small classes anyway, there was no need to appoint someone separately in a permanent position. They had run the school like this for two years and it worked well enough.

Being the youngest of the three women, Louise had at first encountered a great deal of subversive hostility, and a two-faced attitude from the older women she found herself working with. The fresh ideas she had brought with her from the London inner-city schools had received a warm welcome on the surface, but had been constantly stalled when she had tried to put them into action. On more than one occasion, she had returned from a difficult day to her small, one-bedroomed cottage and burst into tears with thoughts of returning home to the south. But sticking to her guns on her good days had seen her through, and she now wouldn’t change Cannich for anywhere else in the world.

She picked up her whistle, and walked out of the classroom through the big double doors of the empty hall into the playground. It was a crisp winter’s afternoon and the sun was beginning to burst through a cloudbank. She looked up onto the mountains surrounding the village. If the weather holds, I’ll go for a walk and clear my head, she thought. There was only another forty-five minutes of school left. The overdue marking and reports on her desk could wait. She had all weekend after all. She looked up again to the ridge of the nearest mountain, lifting her hand to shield the glare of the sun from her eyes. She could now see that there was a lot of activity up on the mountainside, and whole parts of the forest seemed to be moving although she couldn’t make out any individual people. I wonder what’s going on, she thought as she heard the buzzing of a helicopter in the distance.

~

Thomas opened up the back of the Overfinch and helped Meg jump down onto the ground. The forest car park, which had been empty yesterday, was now almost full with Army and police cars, some of which sported large radio antennas. The Jaguar saloon had also rolled in behind them. No one had got out of the car though. The Major-General came over to Thomas.

“I’ve asked some of the Army dog handlers to follow in behind you,” he said. “They’ll follow your lead, and will be under your command. This is new territory for them, so we’re all looking to you really.”

Great, thought Thomas with some concern, although he managed a weak smile anyway. He could see four men with German shepherd dogs standing near one of the trucks. A young soldier in a beret ran up to them and saluted the Major-General.

“Major-General Sir, we’ve finished the first sweep and found nothing so far. The snipers are on hold and it’s safe for the dog team to move in.”

“Thank you Corporal,” replied the Major-General. “So Mr. Walker, it looks like you have your leave. I’ll introduce you to the dog team.”

Thomas followed the Major-General across the car park. The dog-handlers were all wearing the red berets of the British Military Police. As he looked around, he noticed the green berets of the Royal Marine Commandos gathered around a Land Rover with a large radio mast. The other soldiers were from the 3rd Battalion Royal Regiment of Scotland, based at Fort George. It didn’t escape Thomas that they had been well known for their involvement in operation PANTHER’S CLAW in Afghanistan. He wasn’t sure if it was irony, fate or just some marketing officer who was laughing at him right now.

Major-General Fitzwilliam returned the salutes he received as they neared.

“Sergeant Brodie, this is Thomas Walker. He’ll be leading your team and giving you some insight into your quarry. He has experience with this kind of dangerous animal, so take his advice seriously.”

“Yes sir.” Brodie answered.

The sergeant’s smile seemed genuine, and there didn’t seem to be any question or mistrust in his expression. He looked down to see Meg earnestly leaning in to the sergeant’s German shepherd dog, her tail wagging as she licked at its nose in an exuberant fashion. The big dog looked to his handler in confusion, completely unsure how to react to the friendly newcomer.

“Meg has been trained to follow trails and has plenty of experience tracking cats. She’ll let us know if she’s onto something. Keep your dogs on the lead. We know it’s a dog killer and it’s not my intention to put any of them, or us for that matter, in harm’s way. We’ve just got to find it,” Thomas explained to the group of soldiers. He noticed the rifles slung over their shoulders and winced as he realised his was still in the car.

“Sergeant Brodie, do you mind holding Meg for a second. I’ve been given permission to bring my rifle and I need to get it from the car.”

The sergeant nodded, his smile suggesting he recognised Thomas’s nervousness. Thomas trotted back to the Overfinch, trying to stifle his urge to run. He felt like he was back at school, trying to impress the older boys on the rugby field. When he returned, he found Sergeant Brodie down on one knee, both he and the big German shepherd making a fuss over Meg. He smiled and felt his walk slow a little as he relaxed. She had always been better with people than him, cutting through any formalities with a confident wag of the tail.

“Nice gun,” nodded the sergeant.

“Thanks,” replied Thomas with a little pride. “Let’s hope I won’t need it.”

~

The creature had dozed lazily for some time in the sunlight. It had found a fallen tree that had become hollow, offering warm, dry shelter after it had fed, as well as a comfortable place to sleep. It licked its muzzle as it raised its head. It stood up, arching its back and stretching its stiff muscles as it spread its paws against the ground. It turned its attention to the log and left deep, long scratch marks in the damp, dead bark. As it exerted a little more pressure, part of it splintered and broke away. The creature swatted playfully at the log now, rolling it back and forth with its paws and smashing it carelessly with its own weight as it clambered on top. The soft shards of rotten bark would still make a comfortable bed. The creature rubbed the ground with the sides of its face. As it trotted forward, it lifted its tail and squatted, spraying the area with a potent blend of urine and a secretion from its scent glands.

Satisfied the new extension to its territory had been marked, it became aware of its thirst and disappeared into the bracken. Its tail flicked casually above the greenery as its head emerged through a hole in the brush to drink from the mountain stream. It drank steadily and enjoyed the rejuvenating taste of the fresh water. It suddenly lifted its head, completely alert. Its ears pricked forward and it scanned the ridge and tree line behind it. Strange sounds echoed through the woods, the same noises that had driven it to this side of the mountain earlier. As it picked up the barks of the dogs, it slunk back into the bracken. It bounded with silent ease out of the trees and foliage. It looked towards Glen Cannich, the loch and nearest of all, the village itself. It listened intently to the sounds floating up the hillside. Having slaked its thirst, it began to heed its body’s next need and padded forward, heading towards the farms and buildings below.

~

Meg was enjoying herself. She strained on the lead and was pulling Thomas along like a locomotive. Her occasional yelps of excitement were met with the same response from the army dogs behind. Thomas and the soldiers encouraged them further into bouts of barking, and he was glad they understood their role as both noise makers and trackers. He hoped to drive the cat from cover, especially if it was lying up, as most of its kind would during the day. They had left the pathways of the forest behind, and were now working their way up a steep ridgeline with a thick cover of bracken and overhanging trees that formed a narrow, natural track to the west. Meg stopped at the crest of the ridge and barked in triumph at the edge of the bracken. Thomas had suspected she’d had something on the nose as they steamed up the hill, and now he was certain of it. A dog searching for a scent would have zigzagged to find it.

Meg stared intently over the bracken. She stood, balancing precariously as she stretched her muzzle out over the brush. Her ears lifted and she let out a whine of unease. Thomas knew she couldn’t see over the bracken and was less sure of herself now. She flattened herself against the ground and looked up at him. He knew this meant that she wanted to be carried and was afraid of something. Slightly more alert, Thomas carefully peered down the mountainside. Nothing stirred or seemed out of place. He tugged at Meg’s lead gently and she took the hint, getting to her feet again. After a quick glance behind her to check the German shepherds were still close, she trotted forward, this time sticking to Thomas’s side on a slack lead as they headed down the ridge.

~

Louise blew hard on the whistle and slowly the sounds echoing around the playground began to soften and fade. Games drew to a halt and the children began to look in her direction.

“Okay children,” she shouted, “form three lines please.”

They separated into their three classes, some slowly packing away their things with exaggerated displeasure that playtime had ended so soon. Out of the corner of her eye, Louise could see Mrs. Jones and Mrs. Henderson making their way across the playground. Hurry up she thought, it’s cold.

~

The creature had edged its way down the mountain, drawing closer to the warm sounds coming from the village. It slunk along the verge and crept up to the stone river that separated Cannich from the mountainside. It paused, hesitating to enter the new environment. It watched and waited, making sure there was no danger here. Its unease lifting, the creature bounded effortlessly across the warm dry surface and over a wall on the other side. It found that the hard ground naturally silenced its footfalls, and it slipped from shadow to shadow as it followed a tree-lined hedgerow. It heard the two female animals chattering on the other side of the hedge and stalked closer. It could sense their frailty in their laboured breathing and padded nearer. They were sitting on a flat piece of dead wood, and had not heard the creature’s approach. Just as it began to flank them, its nostrils were stung by the strong opium scent that hung about them like a cloud. Its lips wrinkled in distaste and it changed course back along the hedgerow. As it rounded a bend, it picked up the sounds that had first roused its curiosity. It padded silently between two stone columns and froze as it saw movement ahead. It had found its prey.

~

Thomas worked his way down the ridge with the Army dog team close behind. As they dipped below the tree line, they found themselves on a gentle slope covered with bracken. Snowdrops and wood crocus had begun to break free from the earth but were not quite yet in flower. It was beautiful and silent, except for the babble of a stream farther down. Meg gave three short barks. Her attention was focused on the other side of the bracken and Thomas knew she had found something. He turned and signalled to the soldiers. They all raised their rifles in readiness and began to creep forward.

~

Aaron Meeks had taken his rucksack off and was putting his games machine into it, when a movement near the gate made him look up. He started to tremble as he watched the hulking creature strut into the playground. He began to shake with fear as he looked around to see if anyone else was watching. He went to call out but found his voice frozen in his throat. He glanced back again to the creature. It had stopped, and was looking straight at him. Its green eyes were fixed on his. As Aaron stared back, he realised the only thing it could be was a monster. He dropped his rucksack and began to stumble backwards towards the other children. The monster lurched forward with a terrible roar that almost knocked Aaron over. This time, the scream came freely as he ran in terror towards his teacher, Miss Walsh.

~

Thomas and the soldiers spread out over the area where they’d found the smashed trunk and flattened bracken. Thomas could see the clear outline of the bed the creature had used. It reminded him of the grass nests he had seen tigers make in the Sundarbans of India. Meg and the other dogs would not walk onto the bracken or approach the trunk shards, whining uneasily in the presence of the strong territory marking they all could smell. Meg pulled gently on the lead, her nose pointing down the slope.

“Let’s not waste any time,” Thomas declared, “call the helicopter and let them know where we are, and that it might be heading towards more open terrain to the west.”

Their position was relayed to the camp at the car park to pass on to the helicopter, and they began their descent. The village lay below them as the forest swept to the north over the mountainside and into Glen Cannich towards the loch. He paused for a second as he tried to anticipate the route the cat would take. The forest path seemed the most likely. He was about to tug Meg back that way, when what sounded like a scream floated thinly up the mountainside. As a second wail met them, the real route the cat had taken became painfully clear to him.

“Oh my God,” exclaimed Thomas in disbelief as the reality struck him.

He slipped Meg’s leash as did the soldiers with the German shepherds behind. They all began to run down the slope towards the screams.

~

The creature was startled by the sound and movement that suddenly erupted around it. It roared in angry warning as the young animals bolted back towards the older females and the stone dwelling behind them. It pounced instinctively towards the movement in front of it, cuffing the small thing with a swipe of its paw.

Louise watched in horror as something from a nightmare played out before her. She watched as the gruesome, rippling shape sent little Aaron Meeks flying across the playground. He landed in a heap and did not move once he had crumpled to the floor. Before she had time to think, she found herself running, screaming as she streaked towards the boy. Crying out in terror as tears formed in her eyes, she gasped for air and checked Aaron for signs of life. He was still breathing but looked incredibly pale. She turned his head carefully and as she went to pick him up, felt the blood under his clothes. She glanced towards the open doors of the hall, but instinct spun her back round. She stopped dead as she came face to face with something monstrous, and stared into the green flashing eyes of the creature as it stepped towards her, its face distorting into an angry snarl.

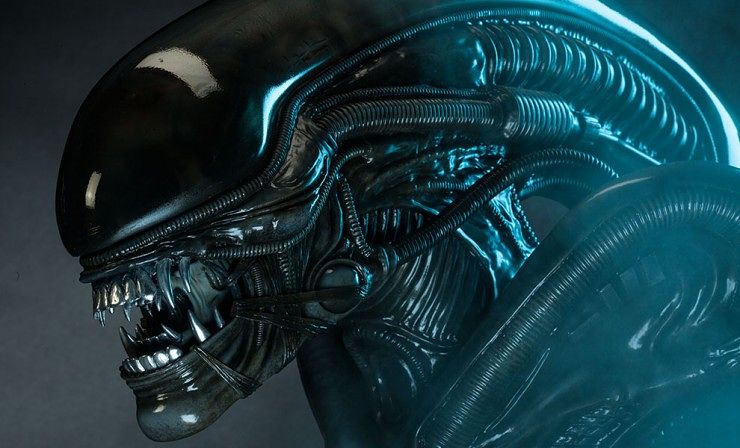

Louise and the creature stared at each other. She felt rooted to the spot, as if she couldn’t move. Instinct tried to pull her away from the hypnotic gaze of the monster. Somewhere in her subconscious, genetic memory of something sinister stirred. It triggered her body, resuscitating movement to her limbs as she took a step backwards and glanced again at the doors behind. Mrs. Henderson ushered in the last of the children, sobbing as they went. She looked desperately towards Louise, but she too was frozen in fear. Louise looked back to the creature. It snarled. The implied menace was clear and guttural this time. It had not come across an open challenge to a meal before, and the snarl was meant as a warning. Louise instinctively knew this, and could see the creature’s intent in its eyes. It wasn’t going to let them leave the playground alive.

Holding the boy tightly with one arm, she fumbled with the whistle that hung around her neck. Taking a deep intake of breath, she blew as hard as she could on it. It had the effect she was hoping for. The creature leapt back in surprise, roaring again at the unwelcome sound, but putting a little distance between them. She began to edge backwards, the whistle still in her mouth. The creature flattened its ears and lowered its body to the ground as it began to creep towards her. She blew the whistle again as hard as she could. The beast shook its shaggy head in displeasure, spitting a roar at her as she edged back farther. Its anger seemed to seep from it and threatened to root her to the spot again. She felt nauseous and dizzy, but fought her fear as she continued to step back. She blew on the whistle again, but this time the creature closed the distance between them, coming within several feet. It now knew the sound wasn’t going to hurt it. Shaking with fear, she almost tripped when her heel hit the concrete step of the entrance. She blew the whistle one more time, the sound lost to the answering roar of the creature as she turned and fell through the door. Mrs. Henderson slammed it shut instantly from inside.

“Take him!” Louise screamed as the older teacher scooped up the unconscious boy in her arms.

She picked herself up and flattened herself against the full width of the double doors. The hall was now empty, and she was sure that Mrs. Jones and Mrs. Henderson had closed the outer doors on the other side of the hall. She hoped they had made it to the classrooms. She wanted as many doors closed between them and the thing in the playground. Even now, she couldn’t quite place what it was. All she could think of was the deep green eyes, and the intelligence and emotion she had read in them. Only then did she notice the sudden silence. She had time for one sharp intake of breath before she was knocked to the floor in a violent explosion of wood and metal, as the creature forced its way through the doors.

The wood beneath the creature broke into shards just like the log had done, and it raked its claws down and through. Louise screamed in agony as if red hot pokers had been steadily drawn across her back. The creature yowled with pleasure as it discovered the soft, wriggling flesh beneath it. It nosed through the shards and bit down. Louise felt the hot breath of the thing and cried out as teeth sliced through her ribs and the top of her shoulder. She sobbed, paralysed and helpless as it dragged her out from beneath what remained of the door. It paused momentarily as it bit down again for better purchase. She choked as blood flooded into her throat from her punctured liver and lung. She used the last of her strength to kick out with her arms and legs, her hands scraping against the right eye and nose of the beast. The creature ignored the mild scratch and calmly lifted its head, carrying her forward in its jaws. It stepped proudly through the smashed doorframe and walked the length of the playground with deliberate caution, never taking its eyes from the far wall as it ignored the screams and cries that met is macabre parade past the windows of the classrooms. When it reached the wall, it hesitated only for a second before leaping. Louise never felt the impact as they hit the ground on the other side.

Now within the darkness of the forest trees again, the creature dropped Louise to the floor. It towered over her. She knew all her strength was gone and that life was leaving her. A last breath moved to her lips. The creature bit down into her skull, killing her momentarily before her body gave up naturally. Satisfied that its kill would resist no more, the creature picked up Louise’s corpse in its jaws and began making its way through the thick cover of the trees.

~

Less than a minute passed before Thomas and Meg entered the playground. He had been pointed in the direction of the school by two terrified old women at a bus stop on the edge of the village. Thomas looked over the empty playground. He saw the fearful and tear stained faces looking out at him from the windows. But it was the blood trail leading away from the smashed remains of the heavy oak double doors that he couldn’t take his eyes away from. He read the scene like a map, from the bashed and broken doorframe, to the shredded door parts, twisted bolts and battered hinges littered over the ground. Finally, his eyes were drawn to the trail of crimson dotted blobs that led to the wall, where they stopped. He had no doubt they would continue the other side and on into the dark shade of the forest. He heard the buzz of the Army lynx helicopter as it rumbled into view and began to circle overhead. He looked up and saw the faces of the soldiers as they returned his gaze, the barrel of the 7.62mm general purpose machine gun silhouetted in outline against the sky. But Thomas already knew they were all too late.

~

You can get your copy of Shadow Beast on Kindle, Amazon, Audible, and iTunes. Find it here: https://a.co/d/7WUVP0j