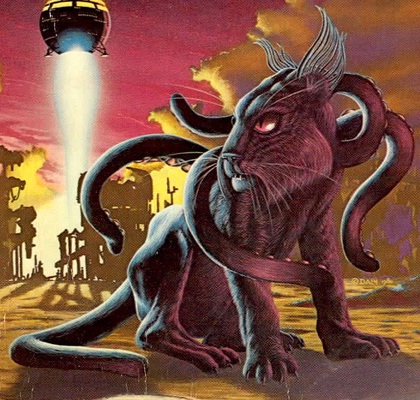

Fear stalked the land, searching out its prey with a single working eye. A scarred beast that prowled the maize fields of southern Tanzania, its remaining eye glowing in the firelight like an ember from the underworld. Wherever it appeared, someone vanished.

By the time the terror ended in the mid-1940s, villagers whispered that as many as 1,500 people had been taken. Some dismissed the figure as impossible; others swore it was true, pointing to empty huts, abandoned farms, and the silence that hung over Njombe for more than a decade.

This is the story of the Njombe man-eaters: a pride of lions whose reign of fear has no equal in recorded history.

A land in crisis

The Njombe District in the 1930s was an isolated plateau of rolling grasslands and scattered farms in what was then Tanganyika. For centuries, lions and people had co-existed uneasily there: lions taking cattle now and then, villagers spearing lions in retaliation. But the balance was about to tip.

At the turn of the 20th century, rinderpest, a cattle plague introduced by imported livestock, tore through East Africa. It killed not only cows but also wild ungulates including buffalo, wildebeest, eland, and kudu. In short, the very animals lions depended on. At the same time, colonial authorities, desperate to protect settler farms and commercial livestock, sanctioned widespread shooting of wildlife herds.

By the early 1930s, the great prey herds had vanished from much of Njombe. For a pride of lions, starvation loomed.

And then the killings began.

The first attacks

Accounts vary on who the first victims were. Some say it was a group of women cutting grass at the edge of the bush. Others tell of a child herding goats. What is certain is that the attacks were relentless.

Unlike the famous Tsavo man-eaters of 1898, which were just two lions, the Njombe killers operated as a full pride, one perhaps 15 strong. They hunted both day and night, stalking footpaths, raiding fields, and dragging victims from huts in the dark. Witnesses described their tactics as disturbingly coordinated: one lion would chase a fleeing villager toward others lying in ambush, while still more lions waited to carry the body off into the bush.

The result was psychological as well as physical devastation. Farmers abandoned their crops. Markets emptied. Whole families refused to travel. A rural economy, already fragile, teetered on collapse.

Folklore takes hold

As the death toll mounted, explanations turned supernatural.

Villagers spoke of Matamula Mangera, a witch doctor said to have cursed the land, sending spirit lions to punish those who had wronged him. Some claimed they saw lions melt into the shape of men; others swore that no ordinary rifle could kill the beasts.

Central to the lore was the pride’s supposed leader: a huge, one-eyed male called Kipanga. Was he real? Many hunters, including those who later fought the lions, believed so. Others argue Kipanga was more myth than flesh. Either way, the stories gave form to a terror that felt inhuman.

Even colonial officers recorded the atmosphere of dread. In their reports, villagers were described as “so paralysed by fear that they would not leave their huts even to tend their cattle.”

The scale of the slaughter

Could the lions truly have killed 1,500 people?

The figure comes up repeatedly, cited by hunters, missionaries, and later by storytellers such as Peter Hathaway Capstick. But hard evidence is scarce. Colonial records were patchy, and many deaths occurred deep in the bush, where no official ever ventured.

Sceptical historians suggest the real toll may have been in the hundreds, easily still enough to mark Njombe as the worst man-eater outbreak on record. But even if exaggerated, the number reflects the lived truth of the time: that whole communities were emptied, and that people felt they were at war with an enemy that could not be seen until it was too late.

Enter George Rushby

In 1947, after years of unchecked slaughter, the colonial government sent in a man who had made a career of battling Africa’s deadliest creatures: George Gilman Rushby.

Rushby was a former ivory hunter turned game ranger, a wiry, hard-driving man used to solitude and risk. He was already known for his encounters with elephants, leopards, and rogue buffalo. But the lions of Njombe would be his greatest test.

When Rushby arrived, he found villages half-deserted, fields lying fallow, and families so terrified they refused to leave their huts even by day. “The district had come to a standstill,” he later wrote. “The people were simply too frightened to live.”

The hunt

Rushby knew killing one or two lions would not be enough. The whole pride had to be vanquished. He organised local scouts, set baited traps, and began a grim campaign through thorn thickets and tangled river valleys.

The lions proved cunning. They avoided obvious bait, circled ambush sites, and sometimes attacked in the middle of Rushby’s own camp. Several times he narrowly escaped, his rifle raised only moments before a lion charged.

But slowly, methodically, the pride was whittled down. Rushby shot some himself, his trackers accounted for others, and poisoned bait claimed a few more. The turning point, Rushby believed, came when he killed the one-eyed male said to be Kipanga. Without their leader, the pride’s coordination faltered.

By the end of his campaign, Rushby claimed to have destroyed the entire man-eating pride. And just as suddenly as they had begun, the killings stopped.

Myth, memory, and reality

The story of Njombe sits at the uneasy intersection of fact and folklore.

- Fact: A pride of lions really did terrorise the region, killing an unknown but horrifying number of people.

- Folklore: A one-eyed demon lion, spirit beasts conjured by witchcraft, an exact death toll of 1,500.

- Reality: Ecological collapse drove predators into desperate behaviour, and human fear magnified their legend until they became almost supernatural.

In this way, the Njombe lions became more than animals. They became symbols of a world out of balance.

Echoes today

Such mass outbreaks of man-eating lions are virtually unheard of now. Conservation measures, better livestock protection, and changing landscapes mean lions rarely, if ever, target humans in large numbers. But the underlying lesson remains: when ecosystems are broken, predators adapt in ways dangerous to us.

Human-wildlife conflict still exists across Africa, from elephants raiding crops to leopards taking goats. The Njombe lions are simply the most extreme and unforgettable example of what can happen when that balance tips too far.

A legacy of fear and fascination

Today, the hills of Njombe are quiet. Farmers tend their maize, children herd goats, and lions are seldom seen. But the memory lingers. Around campfires, elders still tell of the years when lions ruled the night, when entire villages hid indoors, and when the roar of a one-eyed beast froze the blood in men’s veins.

Were they spirit lions? A cursed pride? Or simply predators pushed beyond the edge of hunger? Perhaps all of these at once.

What is certain is that for more than a decade, fear itself had teeth and claws in Njombe. And its story remains one of the most chilling chapters in the long, tangled history between people and lions.

If you’d like to read a fictional story which shares the same elements, then check out The Daughters of the Darkness on Amazon, Kindle, and Audible.

https://www.amazon.com/The-Daughters-of-the-Darkness/dp/B081DNT6N3