The well-behaved monster and the boundaries of respectability.

Awards season is upon us and traditionally, has always had its preferences. Historical epics. Biographical drama. Social realism. Stories that feel weighty before they even begin.

Horror, by contrast, has often been treated as something unruly — too visceral, too commercial, too unserious to sit comfortably among prestige cinema. And yet, every so often, a monster slips past the velvet rope.

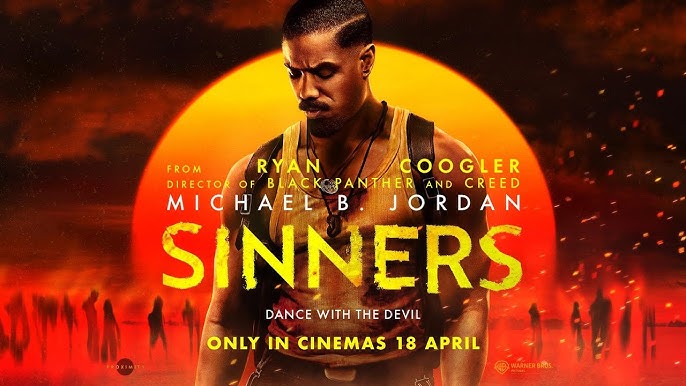

This year, with Sinners dominating Oscar nominations and walking away with major wins at the BAFTAs, that old boundary feels more porous than it once did. Creature cinema is no longer automatically dismissed. It can be celebrated. It can be honoured.

But when monsters win, it is rarely on their own terms.

They are welcomed, carefully, once they have been translated.

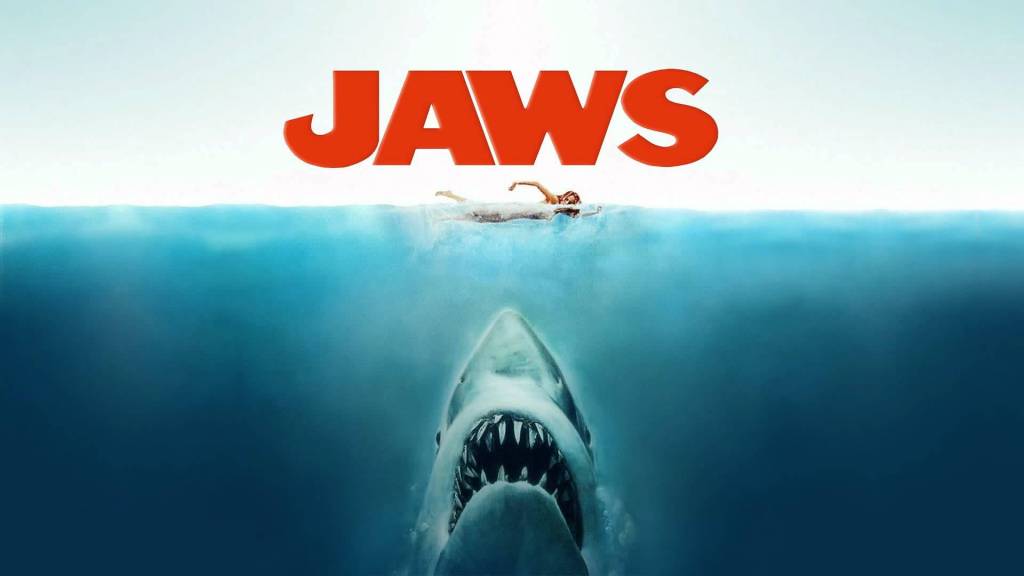

Jaws – The Shark That Wasn’t Just a Shark

When Jaws arrived in 1975, it was a creature feature. A film about a shark hunting swimmers off the coast of a small American town.

It went on to win three Academy Awards — for editing, sound, and John Williams’ now-immortal score.

Not for the shark. The mechanical animal at the centre of the film was never what the Academy formally recognised. Instead, it was the craft that elevated the material: the restraint of the camera, the discipline of the cut, the tension built through absence rather than spectacle.

The shark became something larger than itself. It became:

- Fear of the unseen.

- Bureaucratic denial in the face of danger.

- Economic pressure overriding safety.

In other words, it became metaphor. But beneath that metaphor, the shark remained something more unsettling. It wasn’t malicious. It wasn’t political. It wasn’t traumatised. And it was not misunderstood.

It was simply an animal behaving as animals sometimes do (or in this case, how we thought and imagined they did).

That indifference — that refusal to moralise — is part of what makes Jaws endure. Yet the recognition it received was framed around artistry, not animality. The Academy rewarded how the story was told, not the wildness at its heart.

The creature was tolerated. The craftsmanship was honoured.

The Shape of Water – The Monster Who Became a Mirror

Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water went further. It did not merely win technical awards. It won Best Picture. At its centre is an amphibian creature — clearly inspired by mid-century monster cinema — imprisoned, studied, and ultimately loved.

But this monster does not function as predator. He is not unknowable. He is not ecologically threatening. He is gentle, curious, and capable of tenderness.

He becomes a symbol of otherness — of marginalisation, disability, Cold War paranoia, loneliness. The film invites us not to fear him, but to recognise ourselves in him.

The creature wins because he reflects something human. His monstrosity is aesthetic, not existential. Prestige culture is comfortable with this kind of monster. It can be framed as allegory. It can be moralised. And it can be absorbed into the language of empathy.

The wild edges are softened and the teeth are metaphorical.

When the Creature Becomes Backdrop

A pattern begins to emerge. Horror tends to be embraced by institutions when it performs a certain translation. When the monster is:

- A political symbol.

- A social commentary.

- A psychological metaphor.

- A vehicle for historical reflection.

In these cases, the creature is not truly the subject. It is a lens through which something recognisably human is examined.

The awards are rarely about the animal itself. They are about what the animal represents. And it’s important to clarify this does not diminish the artistry of these films. Many of them are extraordinary. But it does reveal a preference.

Prestige culture prefers its monsters legible and interpretable. In short, it prefers them to behave.

Horror’s Rehabilitation

In recent years, horror has enjoyed something of a rehabilitation. The line between “genre” and “serious cinema” has blurred. Audiences have matured. Filmmakers have pushed boundaries of tone and form.

Part of this shift is cultural. We live in anxious times. Horror provides a language for uncertainty and a release for it — for systems that feel unstable, for threats that feel diffuse.

But institutions still have conditions.

When horror arrives in formal dress — lyrically shot, carefully scored, layered with symbolism — it is easier to recognise as art. When it aligns with contemporary conversations, it feels urgent rather than lurid.

In other words, horror is welcomed when it demonstrates that it understands the rules of the room. It can be frightening. It can be strange. But it must also be respectable. And the vampires in Sinners are polite, well-spoken, and at the very least, wear respectability as a well-practiced facade as a means to an end.

The Uncomfortable Creature

What remains more difficult to absorb is the creature that resists interpretation. The shark that is simply a shark. The predator that is not secretly a metaphor for capitalism, trauma, or xenophobia. The animal that does not apologise for being non-human.

Ecological horror, the stories that centre real animals behaving according to instinct rather than narrative morality — sits uneasily in prestige culture. There is no catharsis in a force of nature. No redemptive speech. No symbolic resolution.

There is only indifference. And indifference is hard to award. It offers no moral comfort. It does not flatter us by suggesting that even our monsters are secretly about us.

Why This Matters

How we reward monster stories tells us something about how we process fear. We are drawn to creatures, but we often feel compelled to domesticate them. To explain them. To soften them into symbols we can decode.

When a monster film wins, it often does so because it reassures us that the monstrous can be translated into something familiar. But some of the most powerful creature stories resist that translation. They leave the animal wild. They refuse to moralise the teeth.

Those films may not always collect statues. Yet they linger. Because they remind us that not everything in the natural world exists to be understood through human frameworks.

Some things are simply other – the literal force of nature. And perhaps that is what true monster cinema has always been about — not metaphor, not allegory, but the fragile boundary between ourselves and the wild.

Awards season may continue to evolve. Horror may continue to gain recognition. But the monsters that win will likely remain the ones that know how to behave.

The rest — the indifferent, the ecological, the untamed, will likely continue to circle just beyond the light. Popular, but not recognised. Always in the shadows of recognised greatness. And there is something fitting about that.

My novels explore similar boundaries between folklore, wildlife, and fear. The monsters are rarely simple. Find them on Amazon, Kindle, Audible, and iTunes.